Solo Dining in Tokyo, Two Mindful Ways

Perspectives on attentive eating, being alone, and finding connectedness in a city.

I love dining alone, so very much.

I find eating by myself to be really enjoyable. I’m sure I’m not the only one who feels this way, given that this is probably an “introvert thing”, and introverts are said to now make up more than 50% of the world’s population.

During a one-day meditation retreat I had attended some years back, we were asked to bring our own food and find a spot at the retreat venue to eat alone during lunch break as a way to practice mindfulness.

I relished every moment of that hour. I ate slowly and paid close attention to the eating experience. I found myself deeply appreciating the different flavours of the food.

At the end of the retreat, we were invited to break silence by sharing our experiences from the day of practice.

One lady confessed that lunch was positively torturous for her.

“I was okay with being alone during the meditations, I was okay with not talking to anyone during rest times… but I was NOT okay with eating alone!” She said almost tearfully.

We learned that eating was always a communal endeavour in her culture. As long as there was food, there would be people gathering, conversing, and enjoying the meal together.

Eating alone at the retreat didn’t bring her peace - it made her feel lonely and sad.

It was interesting for me to hear her takeaway from the experience, because while I do like convening with family and friends for a meal, I have always had a good time eating by myself.

Solo Dining Experience #1

I recently made my first trip to Tokyo, which is supposedly known as the city for solo dining. During the short trip I was offered two precious opportunities to lunch on my own.

Being a vegetarian, I was warned by friends that it would not be easy to find restaurants with vegetarian or vegan options in the city.

There certainly wasn’t an abundance of options, but on my second day there I managed to locate a fairly famous ramen place that had a vegan ramen dish on its menu, and it was serendipitously close to where I was staying.

At 30 minutes past noon, there was a short queue outside the restaurant. I peeked in through the half opened door and saw that the cosy little eatery was packed with groups of people sitting around small wooden tables, chatting and slurping their piping hot noodles with much gusto.

I wondered if they would even accommodate a lone customer. After all, I had been turned away by restaurants a couple of times when I was in Seoul, based on the reason that they couldn’t serve solo diners.

The restaurant service staff spotted me in the queue and raised his eyebrows at me. I gestured a “table for one” with my hand. He asked that I wait for a moment, and a minute later he swung open the door to let me in.

It was a small restaurant, and so every square footage had to be thoughtfully set up to maximise dining space. I saw that each table cluster accommodated four or six people.

I was led to an empty table with four seats. As I sat down, I noticed that my view was being partially blocked by a bright yellow board hanging from the ceiling and hovering over the table so that it served as a divider for some privacy.

A few moments later, a party of two ladies were shown to my table and sat down opposite of me, on the other side of the yellow divider. We were in such close proximity, and yet we couldn’t see each other’s faces. We were together, and also separated.

I compare this experience with the table sharing culture at Cantonese restaurants and cafes, known as “dap toi” (搭台).

During busy hours, we are at times invited or requested to sit at the same table with complete strangers. The space is entirely open, with no makeshift dividers, no physical boundaries established, and no facilitation of privacy. Any successful coexistence during the meal is up to the patrons themselves.

Most times, patrons keep to their own company and mind their own business.

Sometimes, the awkwardness of sharing a table with people we have never met prompts us to speed up our eating, consequently contributing to a faster table turnover for the restaurant.

And then sometimes, perhaps when the vibe at the table feels right, we might strike a spontaneous conversation about how good (or subpar) the food at the restaurant is. Sharing of food would even happen occasionally.

Right after the meal, we would politely bid farewell and leave the restaurant, knowing that this encounter - whether uncomfortable or pleasant - was an ichi-go ichi-e moment (or a “one time, one meeting” experience) that would never happen again.

Now back to the ramen restaurant.

The setup felt a little strange at first, but I soon got used to it.

As I started digging into my bowl of ramen, I was aware that I could easily tune in to my tablemates’ conversation if I wanted to.

But that felt a little intrusive, so instead I shifted my attention to my surroundings, in particular to the yellow board right in front of me.

I immediately noticed that the divider cleverly doubled up as a display for notices, advertisements, artwork, entertainment, etc.

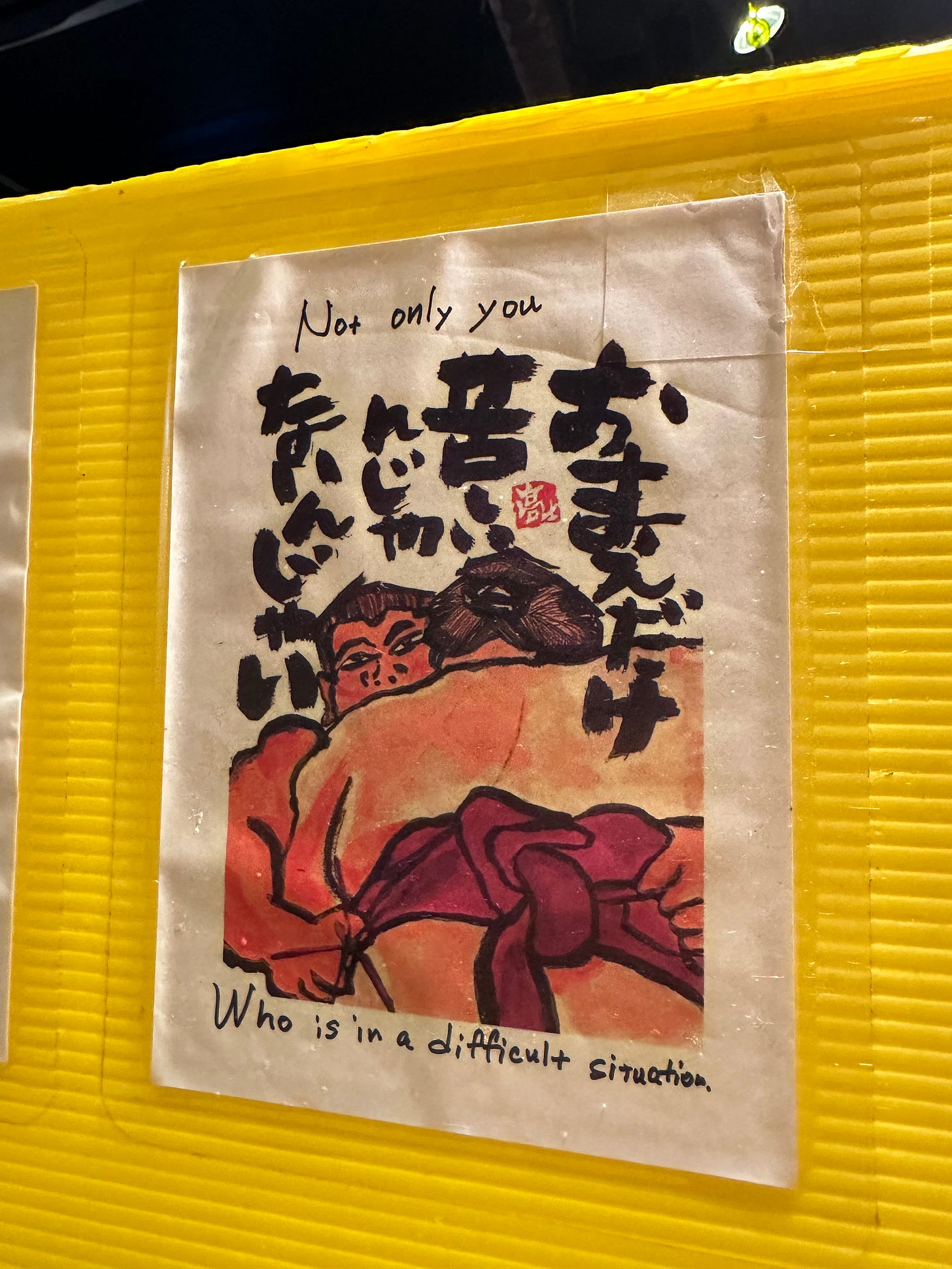

A striking poster of two sumo wrestlers hugging caught my attention. I couldn’t understand the Japanese characters on the poster except for one that read “苦” (pronounced kǔ in Chinese) - which means “suffering”.

Luckily for me, the Japanese text was translated into English:

“Not only you… who is in a difficult situation.”

I looked at the other papers that were pasted on the board; there was a printout of what I assumed to be lyrics to a Japanese song, which Google Translate told me was about not having regrets in life; there was also a beautiful drawing of a sunflower with the words “Hi, Mr. Sun, give me energy!”

It almost felt like those posters were thoughtfully displayed there, perhaps to reduce any boredom or loneliness a diner without company might experience.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mindful Moments with Erin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.